Law & Innovation Lab

The Law & Innovation Lab (the “Lab”) is an immersion study of the landscape of innovation and technology in the legal industry. The Lab provides students the opportunity to gain direct experience at the forefront of legal technology by working to bridge the access to justice gap and improve the effectiveness and efficiency of law practice.

Law & Innovation Lab Overview

Real-World Experience

The Lab offers students the opportunity to engage in the rigorous process of problem-solving and product development. These technology-based products (expert systems, chatbots and document automation systems) will address real world legal problems identified in partnership with local legal services organizations and law firms.

Framed around the product development cycle, the class will begin with a deep dive into design thinking, engaging in discovery and synthesis around the identified problem. Students will then design, prototype, test, improve and refine their digital solutions to the problem. The class will also plan a comprehensive go-to-market strategy to deploy their app into the hands of those who need it most, addressing possible barriers to adoption and community concerns. The class will also discuss, more broadly, ways to encourage the legal profession to embrace product and process innovations to scale scarce resources.

The Lab classroom experience will involve presentations by and discussions with practitioners from across disciplines (legal services, social services, technology, product development, design, and more), along with a heavy dose of joint problem-solving exercises and chat bot, expert system and document automation development.

No prior experience with coding or software development is necessary – just a willingness to think differently, work through detailed directions and engage in creative problem-solving.

Law + Innovation Lab Blog

-

January 25, 2021 - The Law + Innovation Lab is up and running!

The Law + Innovation Lab is up and running!

by Lois R. Lupica

The Law + Innovation Lab (the Lab) will be operating a blog, written primarily by students, that will describe some of the work we are doing.

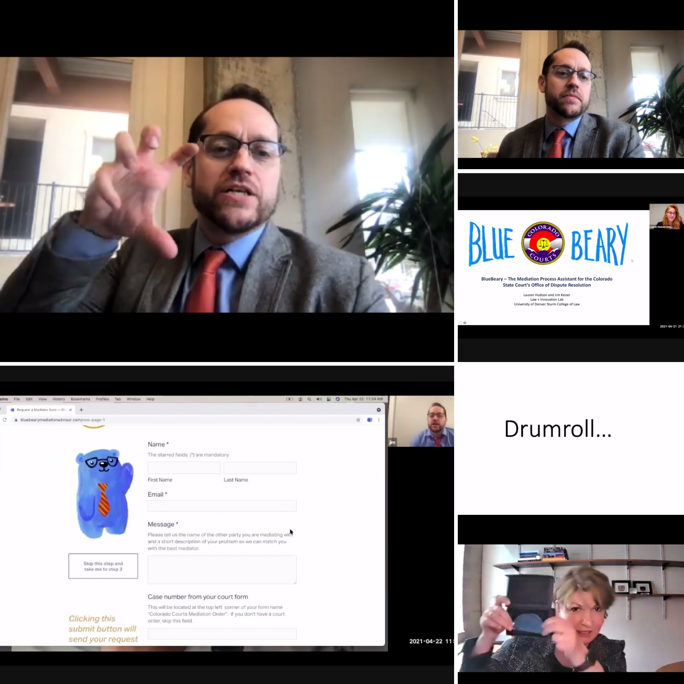

The Lab began its work last week with a visit from Toma Officer, Co-founder and Product Designer of Afterpattern (formerly, Community Lawyer). Afterpattern is a no-code technology platform, designed to help people build legal tech apps, without having to be or employ a software engineer. Toma told us the engaging story of his evolution from a law school graduate to legal tech entrepreneur. The students queried him about opportunities for this type of career path as they showed him the project they just completed – an app that can be used to order a beverage. Toma was wildly impressed with the students’ work (as was I)! With access to just the on-line training tutorials, the projects were a triumph! Creative, aesthetic, technically sound and readily deployable, these apps could be adopted by any coffee house and result in increased service efficiency and effectiveness. Check out this link for an outstanding sample of the Lab’s work (credit to Lab student Robyn Speirn).

Toma then gave the students a tour of some of Afterpattern’s more complex capabilities and walked them through their next project: a database that populates a document template. This app will enable the efficient generation of thank you notes to each of our guest speakers. I look forward to reviewing these completed these apps this week, and to having the class use them to thank our guests for their valuable time and expertise.

Our second guest was Molly French, Manager of Technology at Colorado Legal Services (CLS). Molly spoke to the class about the challenges facing legal services organizations in this time of financial insecurity. CLS has agreed to be one of the Lab’s Community Partners – meaning that a team of students will work with Molly and CLS lawyers to develop a family law expert system that will help those seeking legal assistance in connection with their marital dissolution and child custody issues. This expert system will be housed on CLS’s website and we hope that it will increase CLS’s capacity to serve more people needing legal help.

We also began our discussion of the human centered design process that we will be using to develop legal expert systems. This process is based on the fundamental principle that tools need to be built and tested with the input of those they are designed to serve. We are currently seeking the participation of members of the community for a number of projects. If you know someone who has negotiated a legal issue as a self-represented party and is interested in working with students on system improvement, please reach out to me (llupica@law.du.edu).

-

February 01, 2021 - Real-World Design Thinking Application by Mark Emde

Real-World Design Thinking Application

by Mark Emde

Recently, my fiancé and I upgraded from a full bed to a queen bed and have been LOVING the extra room but ran into an interior design and functionality issue with the previous bed set. Around 2009, I handmade the previous bedframe and it was very customized to a full mattress, so we could no longer utilize the frame for the new bed. Further, the headboard was extremely customized for a full bed, so our new bed did not work as well as the previous bed.

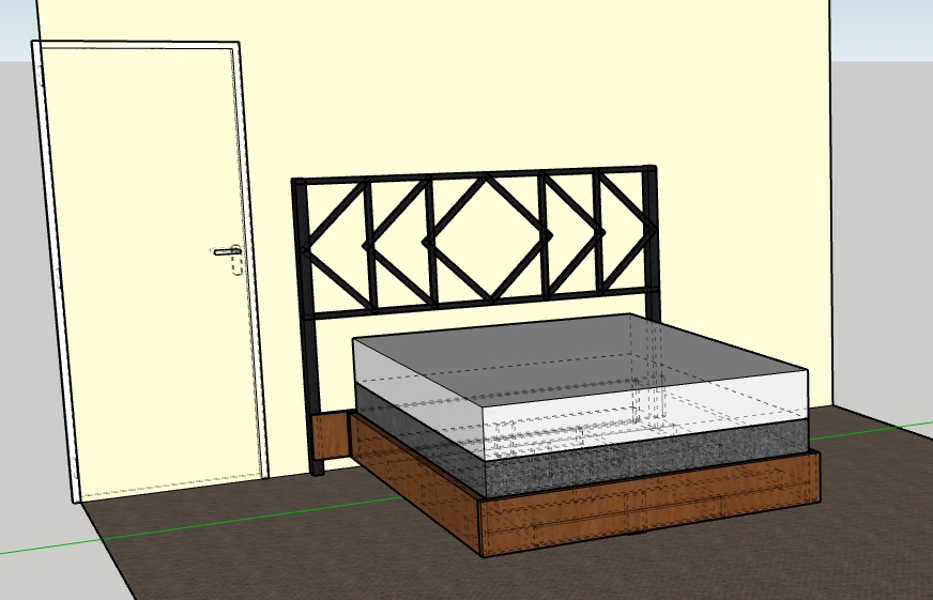

Figure 1. Original headboard with bedframe

The original headboard was part of a roller coaster for a homecoming float that I welded in college. After homecoming, I removed the bridge support and repurposed it into a bed with side tables and lights.

Figure 2. College homecoming float

The headboard and bedframe were two separate pieces and the side tables were designed to accept the custom bed frame perfectly seated between them. When we brought the new bed into our home, not only would the queen bed not fit in the full frame but, the queen bed would not fit between the side tables. A real problem was created…

Figure 3. Headboard with new queen mattress

Now for the fun stuff! When life gives you problems and you are learning about design thinking in your Law & Innovation lab, why not apply the principles to your real world problem? “Design Thinking is an iterative process in which we seek to understand the user, challenge assumptions, and redefine problems in an attempt to identify alternative strategies and solutions that might not be instantly apparent with our initial level of understanding.”1 Further, design thinking involves a solutions based method to problem solving. Design thinking has been boiled down to five phases2:

-

Empathize – Work with your user(s) to understand their needs and desires and challenges.

-

Define – Determine your users’ needs, their problems they are facing, and your insights as to the problem.

-

Ideate – Challenge assumptions and create ideas for innovative solutions to the problem(s).

-

Prototype – Start creating solutions to the problem.

-

Test – Test the solutions and iterate until a final product is created to alleviate the problem.

Empathize

The first step of the process was easy, as I was also involved in the problem we were facing of a headboard that did not accept our bed, that was sitting on the floor resembling a college party house, and also had a three foot gap that was present between the bed and the headboard, where we put a bench to house pillows so nothing fell into the abyss in the middle of the night. The empathy part was easy in this case…

Define

The next step was to determine each other’s needs and define the problems being faced. The true needs were to elevate the bed off the ground and close the gap (and to look aesthetically pleasing, of course). One of the problems I personally was facing was avoiding removal of the side tables and performing any metal work, based on availability of tools.

Ideate/Prototype

This is my favorite part, but can cause frustration if you are not open to the thought process and change that can and will occur during the designing stages. Let the ideas flow! Our first and easiest option would have been to buy a simple metal frame from the furniture store, but that still would not close the gap between the bed and the headboard and there is no joy in buying a metal frame and placing a bed on it. My first thought was to run a small board across the top of the side tables and then pattern wood down the front face of the side tables. This could have worked, but would have made for a large piece of furniture in a small room. After workshopping through ideas and different variations, it became apparent that my fiancé was a very visual person and was not necessarily seeing what I was seeing, or attempting to describe.

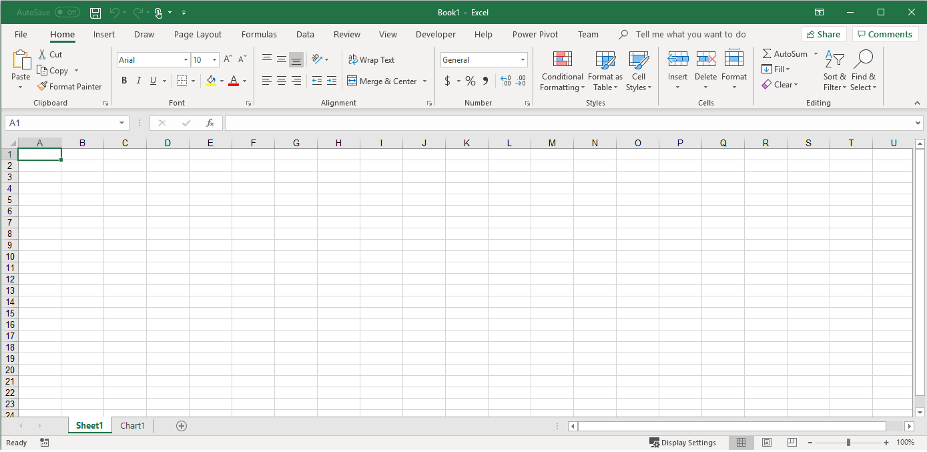

It was determined that pictures needed to be created to effectively solve the bed problem. I used AutoCAD hroughout college and have always played around with it when I can. Google has a great program called Sketchup, which is a 3D CAD program and I figured this would be a great opportunity to try something new and provide visuals. I went to the internet for inspiration of different bed ideas and found some farmhouse style beds, platform beds, and finally, a “floating” bed with lights, how fun!

Figure 4. Inspiration from the internet of “floating” bed with lights

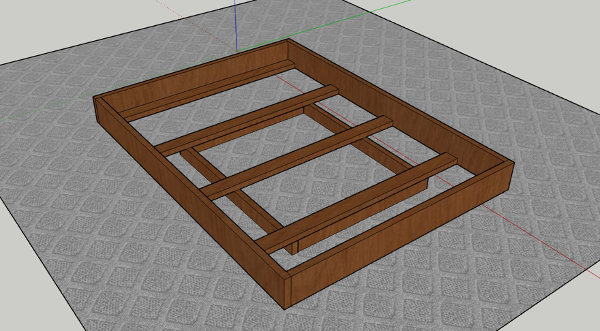

I presented the inspiration to my fiancé and got the nod of approval to move forward with the basic idea. I sketched up the bones of the frame and started the iteration and rapid prototyping process. A first model was created to build off of.

Figure 5. First iteration of the frame

Figure 6. First iteration of the frame showing “floating” aspect

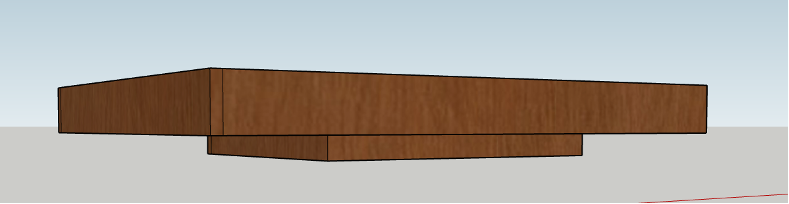

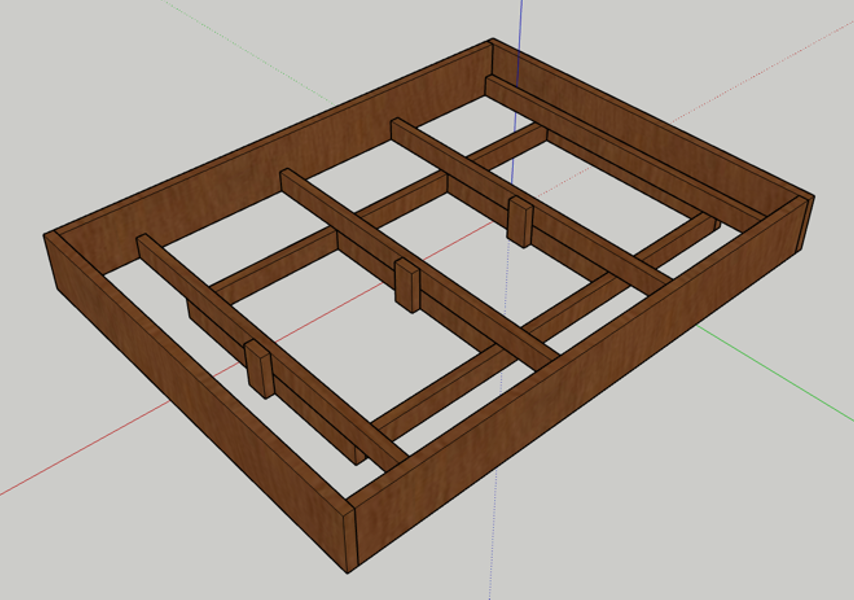

I sent the design to a fellow engineer and got feedback on structural adjustments and aesthetic adjustments, which led to a final version of the frame.

Figure 7. Final iteration of the frame

The easy part of designing the frame was in its final stages, but now the hard part began…what to do with the headboard. One of the main problems of the pillow crevasse still existed and a new problem was created – sharp corners on the nightstand that would leave us with Harry Potter scars on our foreheads, or worse, leaving us blinded from metal to eye impact.

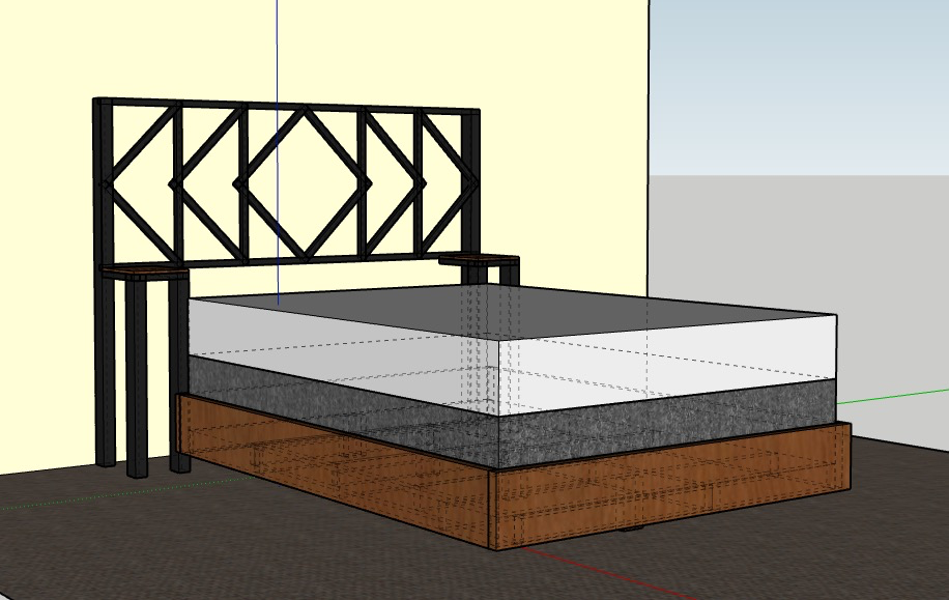

Figure 8. First iteration of bedframe with headboard

After going in circles on what to do, it was finally determined that it would not be that difficult to remove the side tables and that it would only require a couple of cuts, a quick grind, and a light coat of paint. A final visual design was created for the stamp of approval.

Figure 9. Final iteration of the frame with the headboard and no side tables

It was time to move forward with purchasing supplies and to start the initial build. As much as my fiancé hates Home Depot, she was a trooper and tagged along, which I am thankful for, as the original design had an exterior frame made up of 2x10’s and when I started pulling them from the rack was told that she would not like that big of an edge and wondered if there was anything else we could do. Yet another iteration took place and we audibled to 1x10’s, which made for an even more aesthetically pleasing edge.

We got home, made all of the cuts, sanded the edge pieces, stained the edge pieces, cut the side tables off, and began assembly.

Figure 10. Initial build

Through all of this process, one problem still existed…how to connect the frame to the headboard. When I installed the lights on the initial headboard, I ran electrical wire through the metal tube and out the bottom for an easy wall connection. The first time I installed this, I was deathly terrified of not having a solid connection and making a headboard that would shock you in the middle of the night. Ten years later, the fear still haunts me and the last thing I wanted to do was mess with the wiring again, so drilling into the headboard was the last option on my list. After brainstorming and discussing different options, a simple metal strap, wrapped around the headboard support and connected to frame was the final option.

Test

The final assembly took place and it was time to test the bed to make sure the headboard did not fall on top of us, the base did not wiggle, the base did not rotate on the “floating frame”, and to make sure everything was satisfactory. SUCCESS!!!

Figure 11. Final product

Figure 12. Final product with bedding

Review of the Design Thinking Process

When I built the original bed frame, I was a solo designer and worked through all of the issues myself. With the second build, I was not the only one with opinions and ideas of what it should look like. The design thinking process made it simple to work through different solutions and understand what underlying issues and concerns were for each party. The iterating and prototyping stage allowed for visual representations of the final product and created a form of communication to ideate on different designs. The design process is never ending and we are currently working on improving the design we have, as the first night we went to plug our phones in and realized that we had nowhere easily accessible to place our phones. We have started over on the entire design thinking process for side tables and are learning each other’s desires and problems that we are facing. I think we are close to a final design of a box with a hinge that allows access to items that do not need to be visible throughout the day. We love designing together and look forward to incorporating the design thinking process into future projects.

-

-

February 05, 2021 - Could technology from Star Wars be the future of the legal system? by Lauren Hudson

Could technology from Star Wars be the future of the legal system?

by Lauren HudsonWhat if Princess Leia never sent that iconic holographic message to Obi-Wan Kenobi pleading for help? What if any of the main characters had actually followed C-3PO’s advice when he spouted rational, calculated, risk assessments in dangerous situations?[1] These are the thoughts that keep me up at night.

You might be wondering why I am talking about Star Wars on a legal technology blog. This is a valid question. I am painfully aware of how I am outing myself as a nerd, but upon learning about virtual court rooms and artificial intelligence (AI)-based court outcomes in the Law and Innovation Lab, my mind immediately transported to the countless hours I spent growing up watching Jedis and Sith Lords duel in an alternate universe with death stars, light sabers, holograms, and droids. I started to draw interesting parallels between George Lucas’ fiction and 2021’s reality. Let me explain.

First, some context of the United States’ legal system’s relationship with technology is needed.

There is no doubt COVID-19 brought the legal system to its knees. In a matter of weeks, law schools, courts, and firms were catapulted to the present, tasked with implementing technological changes put on the back burner for almost a decade.[2] Remote working and learning is no longer an alternative, it is the new norm. Over the past few weeks in the Law and Innovation Lab, I realized the legal industry has uniquely resisted modernization.[3] But after learning about how organizations such as Afterpattern, Josef, the Colorado Legal Services are harnessing the power of technology and applications (apps) to provide legal services and information to so many underserved communities, I wondered, why the pushback?[4]

My (brief) theory for the industry’s resistance is three-fold: money, power, and fear. While all three motivations go hand-in-hand, each is distinct. First, we learned that technology has the power to reduce a $40,000 legal task to approximately $4500,[5] and while this level of automation increases efficiency and reduces workloads, it also reduces the flow of income. Second, attorneys are considered elite members of society with essential specialized knowledge, yielding great power and status in their respective communities. If a technological system can do the same task as an attorney with more speed and precision, the need for attorneys to perform those tasks is decreased or eliminated, thus decreasing the perceived need for attorneys. Zooming out to a more macro level, another dimension of power is legal gatekeeping; attorneys in power tend to serve those in power and middle and lower-class Americans are left by the wayside, unable to afford or access legal services. The final motivation – fear – splices both money and power. Attorneys raking in the dough have a natural aversion to things that could jeopardize that, and attorneys in great power positions are terrified of things that threaten tradition because tradition upholds the status quo. Legal technology is most certainty a disrupter.

Now for the fun part. The two Star Wars AI-based technologies which I believe may become real-life disrupters are holograms and droids.[6] While there are many ways to define AI, a good working definition is the “simulation of human intelligence in machines that are programmed to think like humans and mimic their actions. The term may also be applied to any machine that exhibits traits associated with a human mind such as learning and problem-solving.”[7]

- Holograms

Imagine a world where the traditional brick-and-mortar courtroom is an archaic notion, a world where 3D holograms allow a physical embodiment of court officers and parties to be viewed virtually anywhere, without taking a step.

Depending on your belief system, this notion could either be exhilarating, repugnant, or somewhere in between. It boils down to a simple inquiry: Is court a service or a place? And if it is a service, is there a need for the physical building?[8]Both now and in the future, rethinking traditional notions of where legal services are offered, and how they are offered, can create opportunities to use technology to increase access to legal services and information to underserved communities who can’t get their foot in the door.[9]

Today, on Earth, legal services providers are trending in just that direction, embracing accessibility and recalibrating modes of resolution. In select jurisdictions, online dispute resolution is gaining traction, where individuals who are experiencing a legal issue can work through an online platform to reach an outcome without ever going to court.[10]These types of online dispute resolutions, at least in Colorado, do not currently produce 2D visuals of 3D displays, or intergalactic teleconferencing for that matter.

However, beyond the legal industry there are a lot of really “strange and innovative types of displays being developed now.”[11] For example, the HoloPlayer One “generates 32 views of a scene from different directions to create a 3D field of light floating above the device.”[12] And “augmented-reality headsets like Microsoft’s Hololens, which overlay 3D images on a user’s visual field, will ultimately provide more flexible ways of achieving similar results” to Star Wars-like holograms.[13]

To be sure, costs for holographic technology equipment would be high. However, in an alternate universe where traditional courthouses are a remnant of the past, it could be feasible to implement. How, you ask? Removing the government overhead of maintaining full-scale courthouses would alleviate a significant portion of funds which could be redirected towards producing and acquiring such technologies.

Using holograms to conduct court processes is a really cool thought, but then again thinking about a judge “standing” in your living room borderlines on ominous.

- Droids

In essence, C3PO “represents the logical man, separated from the emotion.”[14] Some have called this humanesque droid the “diplomatic droid” prototype.[15] These types of droids have an uncanny ability to make swift and accurate risk assessments based on the facts and circumstances.

While I don’t think the role of the judge will be superseded by a robot anytime soon, nor should it, it is intriguing to think about robots like C-3PO as “artificial companions” or more specifically, risk-assessment assistants to judicial decision-making processes.[16]

This idea is not as farfetched as it might seem; the advent of AI-based algorithmic risk assessments are already occurring in criminal sentencing to predict the risk an individual poses to society.[17] Not all risk assessment algorithms are AI-based, but all AI involves algorithms.[18] The primary difference between non-AI-based and AI-based algorithms is that AI-based algorithms are dynamic and have the power to evolve, “creat[ing] an additional set of policy and legal issues over and above those arising in non-AI contexts.”[19]

But with this technology’s transformative power comes warranted concerns.[20] Those who have worked with and studied these AI-based algorithms worry explicit and implicit racial biases are being engrained into the software which assesses criminal risk.[21] It is paramount that the AI-based algorithms are not programed to lead to inequitable outcomes. In order to ensure due process for individuals, three principles are necessary: auditability of the data inputs, transparency as to the risk assessment software, and consistency in risk assessment outcomes.[22]

Beyond criminal punishment risk assessments, however, I opine AI-based droids could have a place in many other court contexts. For example, in the civil realm, the droid could calculate liability fault percentages for damages in negligence lawsuits. It could serve as a real-time translator for parties who speak different languages, one of C-3PO’s strongest traits. It could even play a role in mediating dispute resolutions, one of C-3PO’s humorously not-so-strong traits.

Conclusion

To bring everything full circle, the COVID-19 quarantine has been a catalyst for global change in the legal profession. Forced into remote learning and working, law schools, firms, non-profits, courts are adapting and streamlining services for efficiency and accessibility.

I think that AI-based technology is heading in a really fascinating direction, particularly when it comes to holographic communications and AI-based droid decision-making. If taken to their most positive logical extreme, holograms could revolutionize the notion of courtrooms and increase accessibility to legal services, and court assistant droids could help make equitable legal risk/liability decisions and communicate across language barriers. I admit, maybe Star Wars is not the end-all-be-all inspiration for every technological advancement in our society, especially in the legal profession, but I don’t think it would hurt to take a page from George Lucas’ book.

[1] Thomas Daly, The Han Solo/C-3PO Scale, The Medium (July 11, 2017), https://medium.com/@thomascdaly/a-scale-for-assessing-a-product-managers-skill-set-9a7728a80fb6.

[2] Ralph Baxter, Richard Susskind – How Technology Will Change Justice, Legal Talk Network (Jan. 8, 2020), https://legaltalknetwork.com/podcasts/law-technology-now/2020/01/richard-susskind-how-technology-will-change-justice/.

[3] Id.

[4] Thomas Officer, Law and Innovation Lab Lecture (Jan. 19, 2020); Molly French, Law and Innovation Lab Lecture (Jan. 21, 2020); Sam Flynn, Law and Innovation Lab Lecture (Jan. 26, 2020).

[5] Thomas Officer, Law and Innovation Lab Lecture (Jan. 19, 2020).

[6] Daly, supra note 1.

[7] Jake Frankenfield, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Investopedia (Jan. 6, 2021), https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/artificial-intelligence-ai.asp.

[8] Baxter, supra note 2.

[9] Richard Susskind, Tomorrow’s Lawyer pages (date).

[10] Sharon Sturges, Law and Innovation Lab Lecture (Feb. 2, 2020).

[11] Edd Gent, 5 ‘Star Wars’ Technologies Now Moving from Make-Believe to Reality, NBC Universal (Dec. 13, 2017), https://www.nbcnews.com/mach/science/5-star-wars-technologies-now-moving-make-believe-reality-ncna828906.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Daly, supra note 1.

[15] Jonathan Roberts, Star Wars: These Could Be the Droids We’re Looking For in Real Life, The Conversation (Dec. 17, 2015), https://theconversation.com/star-wars-these-could-be-the-droids-were-looking-for-in-real-life-52285.

[16] Id.

[17] John Villasenor and Virginia Foggo, Artificial Intelligence, Due Process, and Criminal Sentencing, Mich. St. L. Rev. 295, 297 (2020).

[18] Id. at 296.

[19] Id. at 296–98.

[20] Id.

[21] Id. at 297.

[22] Id. at 296.

-

February 12, 2021 - What can spreadsheets and credit cards tell us about the rise of LegalTech? by Thomas Johnson

What can spreadsheets and credit cards tell us about the rise of LegalTech?

by Thomas Johnson

When talking about the reluctance of the legal profession to accept LegalTech, it has always reminded me of a podcast I listened to in 2015 about spreadsheets. Episode 606 of NPR’s Planet Money podcast titled “Spreadsheets!” details the saga of the creation and explosion of electronic spreadsheets in industry and everyday life. So, what do spreadsheets have to do with LegalTech?

This discussion requires a brief recitation of the labors of the accounting profession before the electronic spreadsheet existed. Before the introduction of Visi-Calc (the predecessor of modern-day Microsoft Excel), accountants would use hard-copy spreadsheets to do their calculations. Paper spreadsheets created a clean system for accountants to look at the financials of a business in a methodical way. There was one major drawback to the paper spreadsheet, however.

Suppose the accountant, let’s call him Bill, generates the financial outlook for the client company, and the client wants to know the financial consequence of increasing every employee’s bonus by 2%. Client company had had a good year, and the employees deserved it. For Bill, this meant pulling out his large eraser and erasing all his work to restart the calculations. A full day of the crunching numbers later, and Bill had the client’s answer. This small tweak made Bill’s previous work obsolete and required him to completely restart. Why wasn’t there a better solution?

Dan Bricklin, sitting in an accounting course at Harvard Business School, thought of the idea that would solve Bill’s problem. Utilizing the Apple II computer and pong paddles, Dan created the first electronic spreadsheet. His system now allowed Bill to calculate the financial math assisted by the Apple II, and he could easily make changes to the numbers without having to erase all his work. Now that these changes that used to take a full-day could be made in seconds, client company now had a lot more “what-ifs” for Bill to analyze. The electronic spreadsheet greatly decreased the client’s billable time, so Client company asked more questions. But what would this mean for Bill and his co-workers? Was Bill positioned to lose his job to technology?

While the time it took Bill and his co-workers to calculate the financials for clients went down drastically, this opened them to being able to run different scenarios for the client. Accountants could now answer all the “what-ifs” and find the most efficient solution. Since 1980, the introduction of the electronic spreadsheet has allowed the accounting profession to flourish, adding around 600,000 accounting jobs in that time. The services were now cheaper and more efficient, so this led companies to want more information leading to greater job security for accountants. However, the introduction of new technology was not without consequence. Around 400,000 accounting clerks and bookkeepers were forced out of the accounting profession. Dan Bricklin realized that his invention would force people out of their jobs, and this was something he had to come to terms with.

How Does This Apply to LegalTech?

Like the accounting profession in the 80’s, lawyers today are fearful of losing their jobs to technology. This is not a new story, and this story will be relevant in many other industries in the future. However, the spreadsheet only created more opportunities for accountants, and I think that LegalTech will have the same effect on the legal profession. LegalTech will only lead to the opportunity for more. This means higher quality, greater customization, and more options.

By automating routine assignments, lawyers will have more time to create high-quality customized legal products and explore the “what-ifs” of the legal profession. Most lawyers will tell you that time is a major factor that affects the product they deliver to clients. Deadlines need to be met, and the quality of the legal work can suffer because of this. Through automation, lawyers will have more time to develop their legal solutions and go down the rabbit holes that they were once unable to follow.

The cost of developing an optimal legal solution will decrease, so consumers will buy more of it. Just like the accounting clients of the past, legal service consumers will now want to know what options are available. Instead of one lawyer working on a trial or acquisition, there could be a team of several lawyers developing different solutions for the client to choose from. Consumers will ask more questions and look for more options leading to a higher demand for legal professionals. This is a win for both lawyers and consumers, opening the door for more creativity, more quality, more customization, more opportunity.

While job loss is likely inevitable, LegalTech will only increase the demand for lawyers. The loss of jobs is something that LegalTech entrepreneurs will have to face. While I am sure they do not want anyone to lose their jobs, it is likely that paralegals and bookkeepers will be phased out of the legal profession. LegalTech will have to come to terms with this. However, the introduction of spreadsheets increased the total accounting workforce by about 200,000 jobs since 1980, and the rise of LegalTech will only increase the demand for lawyers. The job prospects for lawyers will only grow because of the opportunity for more, created by LegalTech.

Another story that I feel parallels the rise of LegalTech is one that I heard from Episode 730 of Harvard Business Review’s Ideacast podcast titled “Square’s Cofounder on Discovering – and Defending – Innovations.” In this podcast, Jim McKelvey, the co-founder of Square, details the pricing problem of credit card services and the creation of Square. What can Square tell us about LegalTech?

Jim McKelvey had a problem at his glass studio in St. Louis. No, there was no glass shortage, and the workshop was not burning down. Someone wanted to buy one of his hand-crafted pieces, but the patron was unable to buy it. The buyer only had American Express, and Jim’s studio only accepted Visa and Mastercard. This was money that Jim was losing. The buyer wanted his piece, and Jim wanted to sell him the piece. The breakdown was in the technology. Why was there no solution?

Jim found out that small businesses had to make about $10,000 a year to afford a credit card reader for all types of cards, and this was pricing out consumers. $10,000 was the end of the market for credit card services. It did not make sense for small and part-time businesses to accept credit cards. It was just too expensive. Jim wanted to drive that price down to make credit card services accessible to more small businesses. He was lucky to be friends with Jack Dorsey, co-founder of Twitter, and they set out to move the end of the market. Was this possible?

Jim and Jack were solving a totally new problem. They had no business model or technology to use as a template. This forced them to innovate several times and create an “innovation stack.” One solution led to two problems, so several different new and innovative solutions had to be discovered to make their solution work. The layering of these solutions led to a stack of about thirteen or fourteen innovations, creating a very complex system. Jim and Jack successfully created Square, a credit card reader that could be plugged into a phone. Something no one had ever heard of. Were they “disrupting” the credit card services market?

Jim would tell you no. While they created new technology and were able to add new consumers to the market, VISA, American Express, and MasterCard continued with their normal business. They were not changing the way that the behemoths of the credit card world were operating. They were simply moving the price point of using credit cards down. They were opening the market to new consumers that wanted the service but found credit cards cost prohibitive. The end of the market had now moved, and Jim and Jack were able to provide a service to people that wanted it but could not afford it.

How Does This Apply to LegalTech?

Jim McKelvey would not say that he “disrupted” the credit card services industry, and I don’t think that LegalTech will “disrupt” the legal profession. Square found a way to remove the cost barriers that consumers were faced with. While major legal service providers will likely continue in their usual business, LegalTech will remove cost barriers to legal services and drop the market end, enabling lawyers to provide services to a larger market.

The major law firms and powers of the legal profession will continue about their business. While they may develop new processes and use some of the solutions that LegalTech has to offer, the high-end of the legal profession will continue to have the same clients and charge the same fees. They do not have a major incentive to change the way they practice law. The rise of LegalTech will increase the quality and customization of their legal work, as discussed above, but if their clients are willing to pay these fees, big law will continue as it has. The major change will come for the small law firms and solo practitioners.

The use of LegalTech will enable smaller firms to offer legal services at a lower price. Through automation, bots, and other solutions, they will be able to lower the price of the end of the market, thereby allowing more consumers who want the service but cannot afford it to enter the market. Small and solo law firms spend a major portion of each day networking, bookkeeping, and finishing administrative tasks. When these processes can be automated, these smaller outfits can offer more services to more clients at a cheaper price. This is not a disruption of the legal profession. LegalTech is dropping the price and adding consumers to the market, just like square did for credit card services.

-

February 23, 2021 - Drinking from the Fire Hose: Innovation Could Help Control the Chaos for In-House Legal Departments by Robyn Speirn

Drinking from the Fire Hose: Innovation Could Help Control the Chaos for In-House Legal Departments

by Robyn SpeirnSetting the Scene

After a few (or more) years of working in a law firm, attorneys often seek to move in-house, partially as a way to get out of the pressure of billable hours, the late nights, and to gain some work-life balance. Interesting work, a predictable schedule, the chance to be a part of a strategic team are part of the extra bonuses that lure attorneys. Those things can happen, but it is not all green grass and roses.

In-house legal departments are cost centers for the business and just like many corporate departments, they are being asked to do their jobs with fewer resources. Whether it is fewer attorneys or fewer support staff, it takes its toll and eventually that attorney that came for the work-life balance is working late into the nights, weekends, and holidays. I have seen it happen in my own company’s legal department and at times, as contracts manager and now law clerk within the department, I find myself logging in at night or on the weekend to respond to the urgent questions or contract reviews because I know that the normal working hours are often filled with managing the fires that seem to come from all corners of the business.

In addition, rather than decrease with the pandemic our workloads have increased. Understanding the legal implications from new laws regarding employees, managing the legal aspects of business contracts that have been impacted by inability to perform work, negotiating real estate contracts for space no longer required and/or alternate spaces and the list goes on. Just last week a customer notified us that they would test any of our employees coming onsite to perform work for Covid-19. This brings in a whole range of privacy and employment law complications and of course the in-house department for the customer is managing the risks they have if a supplier employee were to bring Covid-19 into their facility.

Further complicating the environment is the negative connotation that exists in business in reference to legal. More than once I have been told that legal is the “department of no” which makes it very hard to partner with those businesspeople to do what is best for the business.

Exploring the Possibilities

Businesses often speak of innovating to survive. Coming up with new products, new methods, new services in order to provide its customers with what they need or want. They often look to innovate processes like quoting, customer management, financial systems, and marketing but somehow, legal is often left behind. Or, more likely, legal does not jump on (and often resists) the bandwagon. But jumping on the bandwagon can not only improve the entire workday for the legal team but it can help them be a better, integral, part of the larger business team.

As in-house counsel we may work with the business’s customers, but our customer is the business and as such, we would be well served to keep a mindset of customer focus. Our customer may take the shape then of our shareholders and senior managers, but it is also sales, finance, engineering, service, shipping, and others. In order to create a solution that both helps legal and serves the needs of the customer we must put ourselves in their shoes. What does our customer need and how can we best provide this?

The biggest challenge, at least in my company, is with sales. They do not view themselves as having any responsibility or capability in negotiating the legal contract. Their job is to sell. From legal’s point of view, the sale doesn’t end when the handshake happens (pre-Covid of course!) but when the contract is signed and performance begins. Other challenges that the sales group faces are being put in the place of having difficult conversations with their customers, not enough time, lack of understanding of the why behind the legal issues, delays in the overall sales cycle. Having started in sales, I understand some of those challenges, especially the ones related to not understanding the legal issues. Terms like “best efforts” and “time is of the essence” sound so innocuous but can have significant consequences.

Another department that can benefit significantly from rigorous legal processes is finance. Perhaps their issues are more detailed. Invoicing and payment terms and incoterms affecting costs and revenue recognition are two of the most often seen. These may seem minor but small differences in margin and costs across a large number of contracts can make a big difference in the bottom line. Cash is king as they say so bringing in the cash earlier makes the finance group happier.

Using innovation to solve the problems.

So how do we address these problems? It is clear that whatever solutions we find must be easy to use, take minimal time, and return an overall benefit to user as well as the in-house legal department. Most importantly, our customer must be willing to adopt those processes and tools.

Over the last five years my boss and I have worked to adopt tools that make our workday a little less crazy. The first of those tools was rolled out a few years ago and has largely been adopted across the organization without pushback. There have been challenges but that is more the result of stubborn people than the tools provided. Those who use it well generally find it easy, certainly easier than the prior solution of a Word form to be completed that the user needed to keep track of and ensure they were using the right version.

I think the relative ease of that first implementation led me to skip key steps in a more recent implementation resulting in protracted adoption that is still resisted to this day. About a year ago I designed and implemented a new process, two of them actually, to handle non-disclosure agreement requests. I planned, designed, prototyped, tested, and implemented a process to submit the requests and related documents to the legal department. It works pretty well when people use it. Therein lies the problem. It has been a year since it was first introduced the process to the business, but we continue to have to re-direct requests to the process. In the design phase I did not seek out input from the users and have not (yet) directly sought feedback on the tool. Further, it is a lone tool in a sea processes that gets lost in the daily chaos when the need to use it arises. As I delve more into design thinking, I realize that I may have been able to head off some of this if the users had been consulted earlier. I might also have prioritized other future tools that help to quell the confusion.

That future tool I mentioned previously was launched last month in the form of a legal intranet page with links to the current tools and will be the holding place for all future tools. Instead of users submitting most types of legal requests via email, they will proceed to the intranet page to find the right tool for their need. This allows the user to have a one stop resource and a suite of tools which will guide them into providing all of the basic information we need to get address a matter and stops the back and forth of emails to gather the information. It also means they do not have to remember what information they should be providing, a win for all.

The possibilities for further innovation are only limited by our own creativity and willingness to look outside the traditional legal services model. We continue to envision new tools to reduce the chaos tools for other repeated requests are either in process or being considered. Based on the lessons from the past and on the design thinking we are learning about and putting to use in our class, the process to develop and implement the ideas will become a more rigorous and thought out process in and of itself which will likely result in far more innovative and successful tools.

-

February 28, 2021 - How Simplified Drafting, Focus on Relationships, and Technology are Improving and Modernizing Contracts by Charles Wood

How Simplified Drafting, Focus on Relationships, and Technology are Improving and Modernizing Contracts

by Charles WoodContract drafting has long been a key aspect of the legal industry. Any company entering a commercial agreement wants to make sure they put into writing the terms of the deal as a way to make sure they are getting what they agreed to and protecting themselves if the other party is not holding up their end of the bargain. The larger and more complicated the agreement is, the more vulnerable a party becomes to a lapse in performance or a costly mistake. Imagine an agreement spanning several years and multiple millions of dollars. The interested parties would want every part of the contract to be airtight considering the considerable commitments involved and the increased risk the contract may not provide for an unforeseen possibility. Even simple agreements can be vastly important to a small organization and extremely costly if they fail or are never created in the first place because of a financial barrier to legal services.

Failing to draft and manage legal documents with accuracy can become expensive. The International Association for Contract and Commercial Management determined that organizations lose 9.2% of revenue each year due to poor contract management and oversight.

The contract drafting process is costly in part because of the drawn-out back and forth between legal representatives and complicated language that often comprises the agreement. The typical approach toward contracts, especially those between companies, rely on the idea that they are put in place as protection against the other party. The concern is that one party may find ways around the language to maximize their benefit at the expense of the other. This is described as the hold-up problem or the fear that one party will be held up by the other. Agreements are created with an adversarial mindset anticipating friction. As a result, the purposes of the contract and cooperation between the parties can become hindered by their interest in protecting themselves. Shading is retaliatory behavior in which one party stops cooperating, ceases to be proactive, or makes countermoves when it is not getting the outcome it expected from the deal and feels the other party is at fault. The complicated language also makes it difficult for the people actually executing the terms of the agreement – usually people without legal training – to comprehend or interpret the language. The contract exists more as a safeguard and less as a guide.

In addition to conventional contract language, the cost of contract drafting is exacerbated by the law firm pricing model. For many years, the best way for companies to make sure their contracts were created, implemented, and monitored properly was to hire law firms to oversee that work. However, this of course comes with the expenses associated with a traditional law firm. Law firms may charge companies thousands of dollars in fees to create agreements with any degree of complexity above standard forms. Attorneys scrutinize the language for every possible contingency, working with their clients to learn the relevant information and objectives of the agreement they are creating. The idea is that they are applying their expert, specialized knowledge to the specific case to create a well-functioning agreement. Done at an hourly rate, the cost can quickly add up as the attorney corresponds with the client to incorporate the nuances of the deal into a general contract framework and evaluate the agreement in its entirety.

To make contracts more collaborative, user friendly, and cost-efficient, several innovations in their creation and management have emerged in the legal field.

First, there is a movement advocating for simplification and cooperation in contracts using common goals, plain language, and visuals to shift the focus from convoluted, adversarial language to clearly articulated model for what the agreement should look like in practice.

In a Harvard Business Review article titled A New Approach to Contracts, David Frydlinger, Oliver Hart, and Kate Vitasek argue for formal relational contracts that specify mutual goals and establish governance structures to keep party expectations and interests aligned over the long term. The new approach calls for the parties to have a vested interest in each other’s success by creating contracts with relationship-building elements like shared vision and guiding principles.

The new approach begins by laying the foundation to establish a partnership mentality. This involves transparency as to each party’s high-level aspirations, specific goals, and concerns. The focus is on building relationships at multiple levels as opposed to creating a contract. Then, the parties co-create a shared vision and objectives. This can be accomplished by identifying high level outcomes, immediate goals, and measurable objectives. Next, the parties adopt guiding principles. In this step, the parties commit to reciprocity, autonomy, honesty, loyalty, equity, and integrity to create a framework for avoiding misalignments or tit-for-tat moves when unforeseen circumstances occur after the contract has been signed. By making these principles terms of the contract, the parties create repercussions if any of the ideals are breached since courts may interpret and apply the language in the event of a breach. Then, the parties align expectations and interests. Here, the parties determine the terms of the deal such as pricing, responsibilities, and metrics within the established guiding principles. Finally, the parties stay aligned by going beyond the terms of the agreement and establishing governance mechanisms formally embedded in the contract.

Another method of making contracts more in concert with the relationships they represent is by implementing graphics and language easily comprehended by the people making the agreements. Paul Branch and Stefania Passera at the International Association for Contract and Commercial Management, an organization devoted to improving standards, argue in favor of using visual contracts regardless of the agreement’s complexity. Their idea is that visualization can be just as important as language simplification. By incorporating graphics into a contract, the document can go beyond a document dictating terms and liabilities and become an actively used reference for the agreement and bring clarity and certainty to the relationship. The contract acts as an instruction manual that can be continually used by the parties.

Shell’s marine and aviation business has started incorporating this model into its many contracts created each year. In 2016, its legal department realized that complicated contracts can prevent harmony and their negotiation process can erode relationships cultivated by account managers. The legal department started redrafting contracts using as much plain English as possible and cut word counts by almost 40%. Shell’s marine business also implemented visual contracts. The process involved several phases including benchmarking, engagement with stakeholders, interviews with those affected by contract causes, amendments, simplification, visualizations, and sign-off. Shell restructured their agreements in a way consistent with the new approach described in the Harvard Business Review, where people felt that they were being treated fairly and they could agree on clearly communicated common goals.

Second, technology is changing the legal industry and the way legal services are provided. Thomson Reuters’ 2019 Report on the Sate of the Legal Market notes that services accounting for about 15% of the legal market by revenues are ancillary support services that can easily be performed by non-law firm providers. This means that technology is standardizing and automating typically labor-intensive responsibilities of lawyers.

Technology firms and tools are creating ways to streamline legal services like contract drafting. LexKnights is a firm with a platform that gives businesses intelligent contract generators, which enable them to create legally binding agreements and execute them with an electronic signature, cutting down on the drafting process and allowing the agreement to be entered within minutes and at a much lower cost than a traditional law firm. The platform is able to customize each agreement by allowing the parties to enter information about their company and the agreement directly using plain English inputs. This ensures the correct terms are included in the agreement without the time-intensive and expensive information gathering by a licensed attorney. Law firms are able to provide their expertise when creating agreements, but oftentimes they are third parties without intimate knowledge of the client or agreement. Submitting this information directly into the platform bypasses this step in the conventional contract creation process.

Contract management is another area where legal technology is simplifying the process and reducing cost. Signing a contract is not the end of its use. The contract management process oversees deliverables, deadlines, terms, and conditions while ensuring satisfaction. Contract management platforms allow attorneys and non-legal professionals alike to automate the overseeing of contract implementation while being proactive about possible issues rather than reactive after they arise. According to the Association of Corporate Counsel, contract management and e-signature are two of the top three tools used by corporate legal departments, and the trend is likely to continue because of its accuracy and contribution to productivity.

Programmers at Deloitte legal built dTrax, an artificial intelligence-enabled tool that stores and manages contract negotiation and creation. The tool includes customizable dashboards that can identify contract obligations and revenue leakage. Deloitte’s tax team reports that dTrax was able to save 60% in legal costs. In addition to applying the technology to its own legal agreements, Deloitte has begun offering dTrax to clients as a product or managed service.

Innovation in legal services, both in methodology and utilization of technology, allows attorneys and clients to make the painstaking contracting process more streamlined and efficient while creating better processes for following and managing the agreement. The perception may be that well-established, lucrative professions like the legal industry will be reluctant to adopt practices and tools that have the potential to eat into their billings. However, innovation and progress are inevitable, and the allure of productivity and competition will overcome resistance to change. It was not long ago that legal research was conducted by pouring though heavy, paper volumes of statues and case law. Now, it is difficult to image looking up that information without the convenience and accuracy of online legal research platforms. Changes to contract drafting and management are exciting transformations in the way legal services are provided and will prove to be useful instruments in creating a better product in the legal field.

-

March 8, 2021 - How Artificial Intelligence in Litigation is Changing the Game by Kendrick Davis

How Artificial Intelligence in Litigation is Changing the Game

by Kendrick DavisArtificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly changing the legal game and landscape for several lawyers and firms. In particular, litigation is changing dramatically with the enhanced use of technology and AI. It is helping practitioners with their litigation strategies, saving lawyers time and client’s money, and is possibly changing the way lawyers will be trained in order to keep up with the technological advances.

Litigation Strategy:

AI will help determine the outcomes of cases from the get-go. It is easier for a lawyer to see a case that has a poor chance of prevailing and one that is almost a slam dunk when it is presented to them. However, what happens with those cases that are in the middle and can go either way? Is it 40% likely to prevail? What about 55%? This is what AI can help practitioners solve in the very beginning stages, which can ultimately alter the entire strategy and approach taken to a case.

Once an attorney has this concrete probability, AI can assist further by taking a deeper dive for the attorney to explain the analytics behind it. For example, if AI gives a lawyer a 40% probability of winning a case, AI can dig deeper to determine why that is. Does it depend on the jurisdiction perhaps? Maybe the prevailing cases are bench trials rather than jury trials. This could heavily alter the approach a lawyer would want to take earlier on. There could be a common theme among the winning and losing cases that AI can detect. Ultimately, this would help from a strategic standpoint. Not only would this beneficial for the practitioner, but this is also incredibly useful for the client.

In regard to strategy, it will help determine what routes are more viable and which are not so promising. Maybe a client is wanting to file a motion for summary judgement and the practitioner is unsure of this. AI can input the facts, case law, jurisdiction, and judge to give a concrete statistic as to whether this would be a viable option or not.

Furthermore, this can also give a practitioner and client a starting point in mediations and negotiations. Having statistics and analytics that support the client’s position can pressure the other side and ultimately help give the client the best possible outcome.

Moreover, AI helps draft documents fast and more efficiently. Document automation is not new, but it’s use has been increasing over time, so pleadings and motions are becoming automatic now.

Everybody Benefits:

It is no secret that lawyers work long hours. We’re in a field that is client focused, and we work for the public. This comes with late nights, long hours of legal research, and writing up motions, complaints, memoranda, and briefs. However, the use of this expanding technology will help a lawyer use their time more efficiently and productively.

AI is already being useful in assisting the lawyer with litigation strategy, but it can also assist in legal research. Beyond the standard research platforms such as Westlaw and LexisNexis, AI is ramping up to help take a deeper dive into the law and takeaways of opinions. Companies like Casetext are being used so lawyers are spending less time doing surface level research. This AI instead gives lawyers the valuable information of understanding case law and deciphering the opinions written. Furthermore, the AI can connect the dots between precedent and issues faster than a lawyer can.

With the use of this expanding technology, lawyers will not only save themselves the long hours, but they will further ease future client’s concerns and their wallets. Every hour spent reading, researching, and planning can be cut down with the use of AI. In turn, this cuts down the overall hours that a client is billed for. Clients will spend less money on a more efficient process. Moreover, this will help build the rapport between clients and attorneys. Job satisfaction increases, clients are not worried if they will rack up a huge bill, and this will help ease the tension client’s feel when they talk to their attorneys.

New Training for Practitioners?

With the current wide-spread use of this AI technology in litigation, it is only going to increase across the legal landscape. Clients will seek out those who use this information in order to receive concrete data. Does this in turn mean that lawyers will need to pivot their current approach? There is also the possibility that up-and-coming lawyers will be taught and trained completely differently than those currently practicing.

An attorney in this new world where technology and law are combined needs the proper tools and background to utilize the resources. An attorney needs to be able to manipulate the data entered, change various points, introduce new motions and facts into the AI that is used in order to determine the various outcomes. This means that we need to take steps to improve our access and understanding of how technology works.

Moreover, while data is becoming key, a user of the analytics must tread carefully to not misinterpret the data. This could be a possible trap that lawyers fall into. If one is unable to properly determine what the analytics entail, this could be entirely detrimental to the client. Training in this area might become a vital part in the legal field in the not-so-far away future for law student.

Furthermore, lawyers might end up trying to take shortcuts by using the data. While this will help fast-track decisions, improve accuracy, and assist the process overall, a lawyer without the proper training can take these at face value without considering other possibilities that might arise later on – such as litigating a niche area of law that does not have much case law surrounding it.

Why We Need to Embrace AI and Technology:

While AI is improving the legal system, there are valid concerns presented by those in this industry and, in particular, litigators. The use of AI does assist in several ways, but this does not go to say that AI will completely overtake the practice.

AI can give the tools and assistance to lawyers in several aspects throughout litigation. AI cannot counsel a client in a way that a practitioner can with the use of empathy and fully understand what a client wants from the process. AI and document automation can help create a motion and brief, but it cannot write a better brief and cannot fully express the goals being sought. It will not be able to advocate for the client as well as the practitioner is able to. A machine cannot articulate a client’s story as vividly and persuasively as an attorney is able to. AI cannot think on its feet in a trial and use personality to convince a judge or juror why a certain side should prevail are right.

The goal of AI is not to overtake the legal and vital role of lawyers, but rather to help everyone in this field achieve a new level in their practice, especially in litigation. The goal is to be better, faster, and more productive – not to replace attorneys.

-

April 15, 2021 - Legal Tech Innovation: To Fear or to Embrace? by Micah Hardy

Legal Tech Innovation: To Fear or to Embrace?

by Micah Hardy

What is legal tech innovation?

Nowadays, every law student and the majority of practicing lawyers have come into contact with legal tech and likely use it on a daily basis. Think of LexisNexis, Westlaw, or even e-filing. These are technology-based programs for the legal industry. Legal tech is simply the technology that is intended for use in any part of the legal field, be it a complex case evaluator that utilizes artificial intelligence or a platform that tracks billable hours. Technology is being incorporated into nearly every aspect of our lives and the legal sector is no different.

Innovation is constantly at play in legal tech. It is the process of creating something that did not exist before. This does not have to be an entirely new idea; in reality it usually builds off of and improves (hopefully) something that came before it. For example, legal research via reading physical books has existed for centuries. However, the methods of conducting legal research are constantly evolving. The creators of online legal research tools undertook the challenge of transforming the way in which research is done. As legal research has shifted to an online base, the initial companies have further innovated their own products while competitors have worked to innovate new products that “fill the gap.”

Both LexisNexis and Westlaw have comprehensive and highly complex legal research capabilities. They enable users to find a variety of different judicial opinions, statutes, journal articles and more that a lawyer may need. However, they are rather limited with some state court dockets and filings with courts that are not opinions but still pieces of cases. Then came Docket Alarm. This company realized that the big-name legal research platforms had left some gaps to fill. Given that the majority of litigation occurs in state courts, the founder of Docket Alarm created a platform that enables users to research and track state court dockets, as well as their underlying documents. A user can also find a vast amount of information such as expert witnesses filed in federal court cases that other research platforms have yet to address. Docket Alarm has helped to provide lawyers with a more holistic view of legal problems, as well as the ability to more accurately determine how a case may be decided by a particular judge. It has not negated the usefulness of the big-name companies, rather, it has provided lawyers with the ability to access even more information that may be relevant when reviewing a case or preparing for trial. This is innovation at its finest.

Should legal tech innovation be feared or embraced?

Innovation in the legal industry is a reality whether we like it or not. That said, this is not unique to the area of law. It is human nature to strive to improve; to figure out how to increase efficiency, accuracy, performance, and more. Some industries innovate and evolve faster than others for a variety of reasons. Many say that the legal sector has been slower to evolve, which may be true. Regardless, one cannot deny that the legal sector has evolved drastically over the years as a result of the incorporation and innovation of technology-based solutions.

The fear of innovation seems like it would be better suited if it were called the fear of automation. That is, there is a fear that technology is going to begin to decrease the need for lawyers. This fear may seem logical as many legal tech products are designed to increase efficiency, which leads to one lawyer being able to handle a larger workload than before. Legal research is vastly more automated than it was ten years ago, saving countless hours to dedicate to other work. However, automation is not an evil if you think of where a lawyer’s interests should truly rest: the client.

Lawyers exist to work for their clients. It is our job to help clients through a variety of legal situations and if there are things we can do to better serve our clients, then that is what we should do. Most – if not all – legal tech innovations impact clients. For example, the countless hours that are saved thanks to the innovations in legal research trickles down to clients in the form of cheaper legal bills. That may lead to less money for the firm from one client for one situation, but also creates the opportunity to effectively serve more clients, or to help that one client with more situations.

By focusing our minds on our clients, legal tech innovation is not something to fear, rather, it is something to embrace. Ignoring innovations in legal tech will inevitably cause a lawyer to become less effective and efficient over time in comparison to those that embrace it. Choosing to embrace innovation rather than fear it will help give us reason not to fear the automation that comes with innovation. There is no shortage of legal matters in the United States that require a lawyer’s attention. Those who embrace and learn how to utilize legal technologies with the well-being of their clients in mind will certainly have nothing to fear.

Conclusion

Legal tech innovation enables lawyers to better serve their clients. This should be the focus and goal of every lawyer and ultimately decrease any fear of innovation. Innovation is inevitable and we should not fear that which we cannot control. Rather, we should ask ourselves how we can make the best of the situation. In this instance, we can make the best of innovation by embracing it and utilizing it to be the most efficient, effective, and client focused lawyers possible. There is no shortage of legal issues for lawyers to address–the automation that comes along with innovation simply enables us to tackle more of those issues than before.

-

May 10, 2021 - Discovery: Then and Now by Stephen Herrera

Discovery: Then and Now

by Stephen Herrera

As of now, there are over 100 large e-discovery vendors operating in the United States alone. While attorneys and vendors have always had a tenuous relationship, attorneys, and law firms broadly, are out of their depth when it comes to the problem of how to manage vast amounts of data being sent in from clients at an inconsistent pace.

How did we get here? Before computers and mobile phones, the discovery process was (largely) limited to paper. Anything not on paper was provided by a verbal testimony, or, at most, reference to an object or thing. Because modern technology contains so many repositories of information, as well as types of information, the legal field had to adapt to the growing problem of data expansion.

Take your email client for example. When you look at your mailboxes as a whole, your system will tell you it is X number of gigabytes in size. However, if you are prosecuted or sued for defrauding by way of emails requesting credit card information for a fake service, your mailbox will be subject to e-discovery. A vendor, or even some advanced firms, will take your mailbox through processing. In this process, your mailbox will expand to include the metadata, contacts, and other information that helps your machine run. All of this information, depending on the scope of your case, is discoverable. Because so much more information is held on computers than is held on paper files, we now can more easily manage the information held for discovery. While data management has become easier, we are now faced with the problem of deciding what information needs to be reviewed.

The use of “culling” technology has made this process far easier. Rather than having first year attorneys review every single email you have sent or received for the last seven years, cull technology can batch data based on its type or content. Reviewers can go into a workspace and review a handful of files in the system. Based on how those files are “coded” (where the attorney could mark them as responsive or as referencing the name of the plaintiff), these

systems can now intelligently determine which documents should be reviewed by an attorney or be moved into storage. While useful, these innovations create a series of problems.

How Can Law Firms Manage This?

Answer one is to in-source the entire e-discovery process. While this sounds easy, and could even lead to being able to outsource this service to other firms for revenue, there are major complications with this strategy.

For one, lawyers are notoriously tech-adverse. While the industry is slowly beginning to catch onto the irreversible pull of technology on the marketplace, the vast majority of law firms are still struggling with catching onto tech applications for timekeeping. Until a massive shift occurs across the legal market (pushed by groups such as the Law and Innovation Lab), it is too difficult for all but a handful of firms, domestic or international, to manage both the practice of law and the process of e-discovery.

Secondly, attorneys are largely good at critical thinking, client service, and communication (among other things). Resorting to insourcing e-discovery services relies on the assumption that lawyers can effectively manage an EDRM (Electronic Discovery Reference Model) workflow. While bringing on experts can help clear the massive knowledge gap, firms in this position have now made themselves responsible for an extra business vertical that is difficult to manage. In an age where law firms are not just assigning e-discovery to vendors, but are also outsourcing human resources, accounting, and even client conflict management, it is unlikely that law firms will be able to reverse the trend for a process so core to their business.

Third, it is harder to blame e-discovery hold-ups on an internal process than it is to blame a vendor. The e-discovery process, all the way from initial collection of information to production, can be unpredictable. Further, the rate at which clients provide the information to a firm or vendor can ebb and flow based on the most random of whims. Because of this, the rate

at which data is taken in, reviewed, and produced can be difficult to explain to an end client who wants the information back three days before they provided it. Vendors allow for a stop-gap between firms and clients. Rather than having to tell ACDC Corp. that the vendor is taking a while, and that they will try and reduce their billing amount, firms now have to tell their client that the firm’s internal workings simply can’t meet demand.

Answer two to the larger problem is to work with a vendor. Vendors are specialized in the e-discovery process, can provide a buffer between clients and law firms, and are optimized to run a tech-based service. All of the things that 99% of law firms lack are met through vendors.

How Can Law Firms Manage Vendor Encroachment?

Forget worrying about revenue streams that will never be ours. Legal technology is not the threat everyone claims it to be, so long as it stays in the technology space. How do we determine whether a LPO (legal process outsourcer) service is encroaching too far into the practice of law? We have a simple litmus test for future use that time will not change. If the process could have been done 100 years ago by an attorney, then attorneys should continue to manage that process. While contract analysis and AI-assisted legal research may empower attorneys to advise clients, (I believe) no machine will ever be able to perform the two key functions of an attorney.

First, machines will never be able to synthesize legal research and apply it to the context of a case in the way that a human can. While a machine could eventually be programmed to gather the relevant hits in legal research and compile that against machine language learning to analyze a contract, the information it provides will never capture the intuitive decision-making of a real person. Only a human attorney can take in a client’s needs and assess willingness to negotiate, fear of the process, and understanding of their situation.

Second, machines cannot empathize with individuals. Some clients need to be comforted as they proceed through a painful divorce; conversely, some clients want the zealous advocacy of an attorney that sees the righteousness of their case. While a machine could certainly be programmed to say comforting things, only humans can do more than analyze expressions, tone, and volume. Our ability to connect makes us the attorneys that programs will never be. By focusing on the core functions that we provide as attorneys, tech-based legal offerings should only ever be seen as tools to help us deliver a better product for our clients. For us as attorneys, the end product we provide is guidance through some of the most important times in other people’s lives.

-

August 23, 2021 - How States like Utah and Arizona are Closing the Justice Gapy by Tara Leesar

How States like Utah and Arizona are Closing the Justice Gap

by Tara LessarUnderstanding the Justice Gap:

Globally, approximately 5 billion people have unmet justice needs.[1] In the United States, the Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to counsel for all criminal prosecutions.[2] However, no such right to effective legal assistance is afforded to individuals in civil cases. As a result, effective legal assistance remains out of reach for the majority of Americans.

The justice gap, or the “gap between legal needs and services available,” has the greatest implications for individuals living in poverty.[3]A recent study found that approximately 80 percent of low-income Americans cannot afford legal assistance.[4] This same study found that the middle class is also struggling, with 40 to 60 percent of their legal needs unmet.[5] Without legal assistance, individuals struggle with navigating the complexity of court rules and procedures, as well as with filing court forms.[6] Beyond navigating court procedures, individuals struggle with the substantive law-related issues of their case, which “can lead to the loss of a home, children, job, income, and liberty.”[7]

The COVID-19 pandemic, as well as nationwide uprisings against injustice, have highlighted the weaknesses in our current legal and judicial systems. The pandemic, in particular, raised concerns about the accessibility of the current civil process, especially among pro se litigants. As courts continue to shift through the backlog of cases, it is abundantly clear that there is a need for reforms to make the legal system more affordable and accessible. This post will discuss the limitations of legal aid programs, as well as the innovative approaches that states like Utah and Arizona are taking to mitigate the justice gap.

Why Civil Legal Aid is Insufficient to Bridge the Justice Gap:

The Legal Services Corporation (LSC) is the largest source of funding for civil legal aid for low-income Americans.[8] LSC funds legal aid programs in every state, however, these programs are insufficient to bridge the justice gap because only a small percentage of Americans qualify for legal aid services.[9] To be eligible for legal aid, an individual in 2015 had to make less than $14,713 per year, and a family of four less than $30,3143 per year.[10] As a result of legal aid’s limited resources, low-income Americans received little or no legal help for an estimated 1.1 million eligible legal problems in 2017.[11]

Approximately half of all eligible people who approach an LSC-funded legal aid organization for assistance do not receive help due to insufficient resources.[12] Despite the fact that the number of Americans eligible for legal aid services has increased by 50 percent since 1981, LSC’s funding has decreased by 300 percent during that same time.[13] As a result, 80 percent of the legal needs of Americans living in poverty go unmet.[14]

In response to the justice gap, state task forces and bar associations across the U.S. “have been exploring how the regulation of legal services could be impeding access to justice for Americans, who are increasingly forgoing legal representation or representing themselves in court.”[15] In 2020, the supreme courts of Utah and Arizona approved reforms to attorney regulations aimed at improving the justice gap by allowing non-traditional legal services and providers into the legal market.[16]

Utah’s Regulatory Reforms:

In 2020, the Utah Supreme Court unanimously approved a slate of regulatory reform measures to address the access to justice issue. The Utah Supreme Court established the Office of Legal Services Information, which administers a legal regulatory sandbox (the “Sandbox”) aimed at “overseeing and regulating nontraditional legal services providers and the delivery of nontraditional legal services.”[17]

With the Sandbox, lawyers and non-traditional legal providers have the opportunity to test innovative approaches to delivering legal services with the goal of improving the public’s access to justice. The Utah Supreme Court’s regulatory objective with the Sandbox is to “ensure consumers have access to a well-developed, high-quality, innovative, affordable, and competitive market for legal services.”[18] The pilot program for the Sandbox removes restrictions on lawyers paying for referrals and restrictions on nonlawyer investment in law firms.