DU on the Bench

Sturm College of Law graduates are shaping the judiciary with a focus on serving the public good

This article appears in the spring issue of the University of Denver Magazine. Visit the magazine website for bonus content and to read this and other articles in their original format.

Whether they’re presiding over a municipal court in a small mountain town or serving on the federal bench in Denver, Sturm College of Law alumni are leaving their mark on the judiciary all across Colorado. They can be found in every type of court, managing dockets, instructing juries, listening to arguments and ruling with fairness and impartiality—in other words, ensuring that justice is served.

Below, you’ll meet DU judges presiding over four different courts. While they come from varied backgrounds and career paths, they share judicial expertise and skill, of course, but also a genuine passion for the law and a profound dedication to public service.

That ethic grows out of the law school’s long tradition not just of meeting each student’s educational goals but also of training legal experts who make a positive difference in the courtrooms and communities they serve.

The making of a judge

To retired Denver County Court Judge Alfred Harrell (JD ’71), an active member of the college’s Alumni Council and longtime legal advocate in Colorado, the bench is the “front line” of public service—where effectiveness can be measured by how a judge handles the face-to-face interactions with all those who enter the courtroom.

When Harrell was first appointed to Denver County Court, his mentor, Judge John Kane (JD ’60) of the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado, told him, “We need our best and our brightest on [this court] because that’s where most people meet the judicial system. If they meet a judge who isn’t attentive and who doesn’t care about their situation and doesn’t want to help them, the whole system collapses. I want you to be mindful of that, and I want you to take care of these people.”

In his 30 years as a judge, Harrell never forgot those words. “People would come up to me, months or years later, and say, ‘You sentenced my son’ or ‘You sentenced me,’ and my retort is always, ‘Did I treat you fairly? Were you treated fairly?’ The answer has always been, ‘Yes,’” he says. “That to me has made the whole journey worth it. I’ve been able to reach people, have an impact on them, maintain their dignity, kept them intact, encourage them.”

Ian Farrell, an associate professor at the Sturm College of Law, says the school’s first-year courses on constitutional law and criminal law are “quite well-geared” toward the more technical skills that judges need. “What students are primarily doing is reading cases. They’re reading, judging, analyzing, critiquing, being taught to recognize potential arguments on both sides—a lot of these skills are part of judicial decision making,” he says.

In addition, Farrell says, a judge needs—at the risk of stating the obvious—sound judgment. “You have to be able to ultimately make good decisions. So, you need to have a strong sense of the role of a judge, to what extent does your sense of morality or justice inform your interpretation and application of the law. In a lot of cases, there is a clear, correct answer, but in some cases, there is not.”

Another important trait, says Nancy Leong, associate dean for faculty scholarship and director of the Constitutional Rights and Remedies Program, is the ability to understand the minute details of a particular dispute and the big picture of how the law has evolved over decades and sometimes centuries. “Many lawyers, and I’m going to say some judges as well, have a hard time doing both of these things at once,” she says.

Today’s judges also need an understanding of technology and a willingness to keep up with advancements that may play a role in cases, Leong says. “They don’t have to be on the cutting edge, but you wouldn’t want, for example, a judge deciding a case about smartphones who doesn’t even know how to use their own smartphone. It’s important that judges have experiences that are connected to the experiences that non-lawyers and non-judges have.”

Curiously and perhaps counterintuitively, Harrell says most effective judges he knows did not set out to become a judge. “I’m always surprised when someone says, ‘I’ve always wanted to be a judge.’ I think, ‘What about being a lawyer?’ If you are the best lawyer you can possibly be, there will come a time when someone says something to you or something will happen, and you’ll know [the bench] is the direction you should move in. And then you’ll do the things you need to do to get there, but it’s not really a decision you made—it’s your community, your legal community, making it for you.”

Colorado Supreme Court

Carlos Samour Jr. (JD ’90)

Inside the chambers of Colorado Supreme Court Justice Carlos Samour Jr., a framed movie poster of Chamberlain Haller, the fictional judge from “My Cousin Vinny,” offers this quote: “That is a lucid, intelligent, well-thought-out objection. OVERRULED.”

Clearly, Samour—an accomplished judge, litigator and self-described “people person”—brings a sense of humor to his very serious day job.

Samour joined the high court in 2018, having served as an 18th Judicial District judge for 11 years, including as chief judge from 2014–2018. In 2015, he gained national attention when he presided over the Aurora theater shooting proceedings, one of the largest trials in Colorado history.

Born in El Salvador, Samour learned about the law from his father, an attorney and former judge. He helped out in his dad’s office and was fascinated by the stories he heard clients tell. When he was old enough, he attended his first criminal trial and was “hooked.”

Things took a turn when his father refused a request from a high-ranking military official to bend the law. One night, when Samour was in elementary school, their house was riddled with bullets. Then, when he was 13, his father received a death threat and, without warning to Samour and his 11 siblings, the family packed up their van and fled, going into hiding until they could get visas to enter the U.S. A week later, they embarked on the five-day trip to Denver, where relatives lived.

Samour’s father, then 47, never worked as a lawyer again and eventually took a job as a school bus driver. “That [experience] and what my dad had to sacrifice taught me the importance of the rule of law, and that is something that has stayed with me,” he says.

The family settled in Littleton, where Samour attended Columbine High School. “Everything was different. We were wearing the wrong clothes, we couldn’t understand anything. I remember thinking, I’m never going to be able to speak English.” But he worked hard and, by the time he was a senior, he was on the speech team and was selected to address the crowd at graduation.

The speech team coach had taken him under her wing, spending extra time to help him with pronunciation. That kind of support buoyed Samour throughout his academic career.

After he received his undergraduate degree in psychology from the University of Colorado Denver, a family friend from church put him in touch with the financial services office at DU, which helped him obtain the financing he needed to attend law school. Later, an assistant to Edward Pringle—a former Colorado Supreme Court chief justice who taught one of Samour’s first-year courses—helped him land a research assistant position. That, in turn, led to a federal clerkship with Judge Robert McWilliams Jr. (JD ’38) on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit.

After his clerkship, another DU connection—a lawyer who volunteered to grade papers in Pringle’s class—helped Samour secure a position at Holland & Hart, Denver’s largest firm. It was a great opportunity, but his dream was to work in the public sector, so he left five years later to join the Denver District Attorney’s Office, where he prosecuted cases for a decade.

In the DA’s office, Samour says, he learned “how to be comfortable” in the courtroom—and, ultimately, how to be a judge. “I appeared in front of so many great judges, and I learned different things from each of them. That’s where I learned how to run a docket, how to handle tough hearings, how to keep control of the courtroom without yelling, how to set expectations, all those kinds of things.”

He also learned the “art of disagreement,” becoming friends with colleagues and even opposing counsel—a skill he relies on as one of seven justices on Colorado’s Supreme Court, two of whom are also Denver Law alumni: Chief Justice Brian Boatright (JD ’88) and Justice Maria Berkenkotter (JD ’87).

On cases ranging from water rights and election code disputes to reviews of lower court decisions and cases of first impression, he says, the justices “come together and try to make the best decisions we can as a group. Sometimes we can’t agree, and that’s OK. At the end of the day, we respect each other and genuinely care about each other. Having different perspectives is what makes the court as good as it is.”

Samour credits much of his success to his parents, who encouraged him to dream big, and to all the people who mentored and helped him along the way. When asked what traits have served him well, he points to his ability to get along with people, his work ethic, his down-to-earth nature and his willingness to take risks in his career.

When he agreed to preside over the Aurora theater trial, he says, “People told me, it could blow up in my face, it could ruin my career. It was super scary, but when I feel anxious about something, I dare myself to get past it. It’s kind of like being on a roller coaster. When you’re going up, you feel like you might die, but as soon as you’re done, you want to get back on again. I like that feeling.”

U.S. District Court, District of Colorado

Charlotte Sweeney (JD ’95)

For years, Charlotte Sweeney had no interest in being a judge. Then came the 2016 election.

At the time, Sweeney, who grew up south of DU in the suburb of Littleton, had built a successful legal career, happily leading her own Denver-based law firm focused on employment discrimination and pay disparity cases.

That interest, she says, grew out of a class on the subject with Sturm College of Law professor Roberto Corrada. “It just fit where I was and what I believed and where I wanted to go,” she recalls. “I knew how important employment is—besides family, it’s generally the second most important thing in most people’s lives.”

But after the election, Sweeney recalls, she grew troubled by legal developments. “I felt that, rather than sit and complain about what was going on, if I had more to give, I’d better step up. It dawned on me that [being a judge] might be a good next step.”

Six years later, in the summer of 2022, Sweeney became the first openly gay federal judge in Colorado history, something she says wouldn’t have been possible until recently.

When Joe Biden became president, the White House sent out a memo that was “a call to action,” Sweeney says, for people to serve on the federal bench. “Lo and behold,” she adds, “for the first time ever, they were looking for diverse candidates,” including people with civil rights and employment backgrounds.

“It was just one of those slap-you-in-the-face moments, and I said, ‘OK, I’ll apply, we’ll see.’ I wasn’t sure I believed it—and kind of felt that way throughout the process—but here I am,” she says.

After Sweeney threw her hat in the ring, she was one of a handful of candidates chosen to be interviewed by Colorado Sens. Michael Bennet and John Hickenlooper. They narrowed the pool to three candidates, who went on to interview with the White House Counsel Office in Washington, D.C.

The nomination process—and the ensuing confirmation hearing with the Senate Judicial Committee—was “surreal,” Sweeney says. “It just honestly didn’t seem real.”

When she got the call, she says, “It was terribly exciting. I’m extremely honored to be the first member of the LGBT community here in Colorado on the federal court. It’s always wonderful to be the first, but it is more important that I am not the last.”

Sweeney began her term last August and now oversees a wide-ranging docket that includes everything from a property case involving national forests to one involving a ban on conversion therapy for LGBT youth. “It’s been kind of a trial-by-fire, drink-from-the spigot kind of thing,” Sweeney says. “But it’s been fun learning and adjusting to the different areas of law.”

What has surprised her most is the sheer volume of cases on the docket. Off the bat, she was assigned about 250 cases, with almost as many pending motions. The average time to trial in this court is about 33 months. “That’s not giving proper access to justice,” she says. “My single focus here is moving cases through efficiently and productively, while making sure the parties feel heard.”

Sweeney also takes pride and pleasure in helping to diversify the courts. “As a law student who was basically in the closet, I didn’t have any role models. Monumental changes have occurred just by people being out and being accepted,” she says. “I’m delighted for law students now who have many more doors open to them. I mean, we’re not there yet, but it’s nice that young lawyers are walking into a different set of circumstances than we were.”

Having that representation is also important for litigants. “If you can’t be in front of a judge who looks like you, who is like you, you just feel left out of the system,” Sweeney says. “As we diversify the courts, the public will have a greater sense of confidence in us and the decisions we make.”

18th Judicial District, Douglas County

Theresa Slade (JD ’97)

For Judge Theresa Slade, presiding over a courtroom can be a sobering experience. After all, judges make decisions that profoundly affect people’s lives. But Slade never forgets the role she also plays in connecting with people, guiding them through legal proceedings and educating the community about how the law works.

Slade, a Colorado native, learned about the legal profession by watching Court TV and shows like “L.A. Law.” For a while, she wanted to be on TV herself, perhaps as a law correspondent. But once in law school, Slade discovered a love for the nuts and bolts of civil procedure. “I just loved the problem-solving—all the steps and getting through it. If one piece isn’t in place, the rest falls. That made sense to me,” she says.

In her last year at the Sturm College of Law, she interned for the Denver District Attorney’s Office, and everything clicked. “The cases I worked on were mostly traffic violations, but I thought it was the coolest thing in the world. I thought, this place is magical. The courtroom is magical. This is where I’m meant to be,” Slade says.

She felt she could make a difference by treating everyone—and every situation—fairly. “Speeding tickets, getting a ticket for driving without a license, these are things that matter to people,” she says. “If someone is driving without a license, I tend to think that it’s better for everyone if they get their license, rather than go to jail and then be resuspended.”

After graduation, Slade briefly worked for a law firm doing transactional work, but she missed interacting with people. She left to start her own criminal defense practice and get “back into the courtroom.” Eventually, a judge asked if she was interested in becoming a guardian ad litem, a court-appointed representative who serves individuals—in this case, children—who lack the capacity or competency to act in their own interests. “I was like, ‘Oh, I can represent kids?’ That sounded pretty great,” she recalls.

She took on that challenge and added juvenile defense to her practice. Working with kids, she says, was not easy. “Kids in tough situations are good at building up walls. They push you away, refuse to answer questions, tell you you’re dumb. But they’re just humans—and I’m persistent. You just have to give them the time and space they need.”

As a judge, she welcomes kids into her courtroom. “Kids didn’t used to come to court. People thought they didn’t need to be involved in their parents’ divorce or whatever the case may be,” she says. “But I remember thinking, if I were 7 and my parents were getting divorced, I would sure want someone to know how I felt about it.”

That potential for making a difference drew Slade to the bench. “I saw these great judges doing things that made a huge difference to my clients. I wanted to do that.” She first became a magistrate and then was appointed to the bench in 2012. She’s been retained ever since.

Being up for retention is one of the most stressful parts of her job, Slade says. “People are often voting only for a specific issue or person they’re passionate about, and the rest they just ‘eeny-meeny-miny-moe’ it. Or they don’t think their vote matters, and so they don’t vote at all.”

Slade takes every opportunity to talk about what she does and explain how things work, noting that judges have more freedom to do so now than they once did.

“When I started out, I was told to build a wall, protect myself, be careful who I talk to. No one in my social circles even knew what I did,” she says. But now, Slade is encouraged to connect with the community and help educate people about what she does and the judicial system. She gives presentations at high schools, attends Constitution Day events and participates in mock trials.

“When you take the bar and take the oath to uphold the Constitution, you take on an obligation to help people have faith in the system and to teach them about it,” Slade says. “Whether you’re a public service attorney, a civil litigator, a legislator or a judge, I think you are obligated to teach people around you about what you do, why you do it and why it’s important.”

Vail Municipal Court

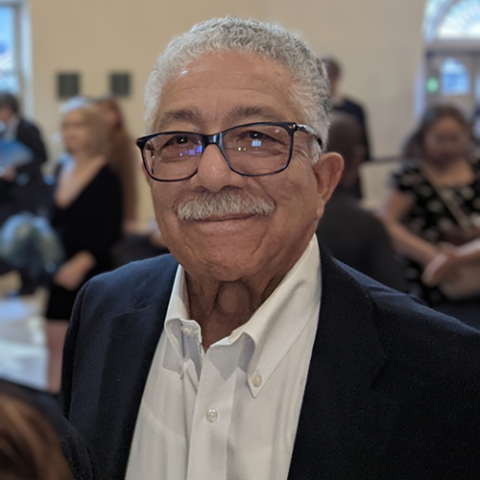

Cyrus “Buck” Allen III (JD ’74)

“You’re always on display,” says Judge Cyrus G. Allen III, known as Buck, of being the one-and-only judge in the town of Vail. Despite its status as a world-class ski destination, Vail is a close-knit community, and Allen, who is in his 44th year on the bench, is not only recognized everywhere he goes but is seen as a steward of the community’s values.

He recalls one Sunday morning early in his career when he went into town to buy newspapers. “There was absolutely no one around. I went to the newspaper rack, put in 50 cents, pulled out a paper, closed the door, put in another 50 cents, took out another paper, and went on my way,” he says. “Six months later, somebody came up to me and said, ‘You know, I was cleaning the shop up above where the rack is, and I watched you buy two separate papers. Most people put in 50 cents and take two or three papers and walk away.’

“I had never even thought about doing something like that, but it was like, gee, even when you think there’s nobody looking, you have to always do what’s right and set a good example.”

As a municipal court judge, Allen takes on that responsibility gladly. He grew up in Denver, but the avid skier has had an affinity for Vail since he was a kid. He attended Dartmouth College for his undergraduate studies, but returned to Colorado for law school, partially, he says, because the mountains beckoned.

After law school, Allen served as a deputy district attorney in the Georgetown office of the 5th Judicial District, which includes Eagle County. When a judge he had worked with needed to take a leave of absence, Allen was appointed as the temporary judge—and he never looked back. “At some point, I realized I’m a better listener than talker, so [the judiciary] was the direction I thought I should go in,” he says.

Serving as the judge in Vail is a part-time job, allowing Allen to also preside as a municipal judge in neighboring Avon and Breckenridge. His docket—made up largely of relatively minor incidents related to traffic, shoplifting, deceptive use of ski facilities, and late-night, alcohol-related “good ideas”—is not, in general, as full as those in other jurisdictions. This allows him to connect with the community more personally.

“I can spend more time with each individual that comes through the court, and I think that’s been valuable,” he says. “What I’ve found is, if you listen to what people have to say very carefully, and you incorporate what they’ve told you in your response, that makes a big impression on them. Oftentimes, even when I’m giving someone a fine or penalty, they thank me. They feel like they were heard.”

Most of those people are “self-correcting,” Allen says. “By the time they come to court, they’ve realized what they have done wrong and have made efforts to fix it, which allows me more flexibility in dealing with them.” For example, he has been known to hand out penalties that require, say, donations to a local food bank or, for juveniles, joining the family dinner three times a week.

Allen also finds that using humor in the courtroom goes a long way. He allows people to tell their stories of what happened and why. Many of these tales are humorous and recounted with vigorous expression. Allen may respond with stories from his own life, some of them self-deprecating, to make his points.

“People are nervous. They don’t know what the judge is going to be like, and it puts them at ease a bit if you can make a little fun of yourself. They realize, ‘Oh, maybe he’s human after all.’”